In the first of this series of posts on the SAT’s Writing and Language section, I distinguished between two broad types of questions: 1) grammar and punctuation and 2) composition and style. Although the test will not explicitly flag questions as belonging to one or the other type, it is useful to be aware of the distinction in order to understand the different methods that each type requires. For the most part, grammar and punctuation questions deal (as we have seen) with the analysis of the constructions of particular sentences and the applications of rules that guide correct usage in these constructions. The correct or incorrect answers can be found by testing the sentence against these rules. Do the subject and verb agree? Is a modifying clause next to the word that it modifies? Does a complete sentence precede and follow a semi-colon? And so forth.

Composition and Style: What are they?

Composition and style questions are different, because they aim not so much at correctness with respect to a set of rules, but rather at higher-order goals such as clarity, coherence, and persuasiveness. In this post, I will offer a way of approaching these questions. My goal will be to show that, even though we do not have a body of set rules to look to as for grammar and punctuation questions, there are nevertheless methods that will allow you to reliably find the right answer. Although there are several specific kinds composition and style questions (your tutor will cover them with you), the following should offer you a way of puzzling through all of them.

A Method for Composition and Style Questions

1. Finding the task

The most important thing to do when approaching any composition and style question is to identify the task. Look for language in the question that indicates what exactly you are trying to accomplish: Complete an idea? Set up the following sentence? Offer a specified detail or logical connection? It is important to determine the task at the outset, because it will guide you in the next two steps of the method for tackling these problems: 1) evaluating the context and 2) identifying the key ideas in the answer choices that will provide a concrete solution to your problem. If you come up with the wrong task, you may find an answer that “works,” but not for the task that the test asks of you. It will therefore be wrong.

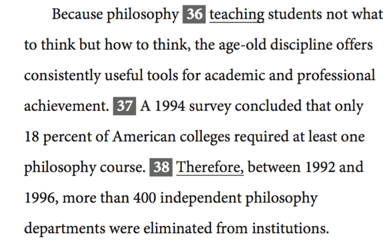

Before looking more closely at context and key ideas, it will help to offer a sample problem from one of the practice SAT exams. First the passage:

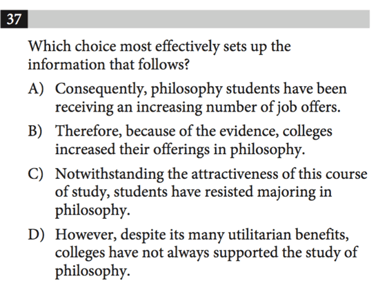

Next, the question:

After reading the question, we see that our task with this problem is to find a choice that “sets up” the sentence that follows [37] in the text.

After reading the question, we see that our task with this problem is to find a choice that “sets up” the sentence that follows [37] in the text.

2. Reading the context

Now let’s look to context. It is preferable to keep the context as narrow as possible. That will block out extraneous information that might distract you, and also help focus your attention on the most important information the passage. Here, we determined that our task is to provide background for (“set up”) the following information. The context that most concerns us, then, is what follows [37].

Note that different tasks will require you to look to different parts of the context. If you are asked to provide a conclusion or complete a logical or rhetorical sequence, you will need to give more weight to what precedes (especially if you are adding the final sentence in a paragraph). If you are asked to provide a transition or logical connector, on the other hand, you will need to give equal weight to both what precedes and what follows.

Keeping our task in mind here, we are most concerned with the sentence “A 1994 survey concluded that only 18 percent of American colleges required at least one philosophy course.” Now that we have identified the significant context, we read it closely not only for the information that it conveys—its subject, object, etc.—but also for logical connectors that might give us an idea of how it relates to other sentences. In our case, we know that we need to insert a sentence before this one: is there anything in the context that will help us know what that sentence should look like?

First, we notice that “colleges” is the subject of the sentence, but that it does not show up in sentence [36]. We need a bridge from the general statement about philosophy to the narrow statement about college policy. Moreover, the word “only” provides us with an important logical and rhetorical clue. The word indicates the surprising or significant smallness of the figure (“18 percent”) that follows. It would hardly make sense for the author to emphasize in sentence [36] the value of studying philosophy only to assert immediately afterwards that so few people study it. The relationship cannot be one of cause or result, then, but must instead be a qualification (= a restriction) or concession.

In general, by the time you are done identifying the task and evaluating the context, you should be able to describe roughly what you are looking for in terms of a solution. You don’t need to use abstract words in this description (“cause,” “result,” etc.), but it will help if you are at least able to determine what kind of concrete language (such as “but,” “because,” “however,” etc.) could form a step towards solving the problem.

3. Using key ideas

With the task and context puzzled out, we now need to choose an answer that will solve our task. One way of finding out which answer most effectively addresses the problem is to focus on key ideas in the answer choices. We will call a “key idea” an idea that directly relates—logically, rhetorically, or by offering a concrete detail—to the problems that we have identified in context.

We noted in our sample problem that sentence [38] presents a contrast, concession, or qualification with (to) what precedes. We need to find an answer choice, then, that paves the way for such a contrast; or to put it differently, we are looking for the key idea of a logical contrast in the answer choices. Other information is, for the time being, on the backburner. There are in fact “logic words” at the beginning of each answer choice A–D that sharply distinguish the sentences from one another. Looking more closely, we see that A and B are off the table because they show a relation of cause, not concession or contrast. C and D are better, but how are we to choose between them?

Here again we lean on our reading in context and resort to another key idea. We determined that we needed something that would provide a bridge from a general statement about the value of studying philosophy to the narrower statement about college policy. Our key idea, then, is college (policy). Only D mentions college. C mentions students, and thus provides the educational background that we need, but lacks anything that would provide a transition to the idea of college in the next sentence. D is the correct answer, because it is the only choice that contains both key ideas we identified earlier in the process.

Wrapping up

As always, practice is crucial for turning theory into success. I hope that this method will give you something to relate your experience to on your way to mastering these kinds of questions. But while the ideas presented above will help structure your approach and provide a common vocabulary for discussing with your tutor why a given answer is correct, it is ultimately repetition and exposure to the full range of question types that will prepare you for the test.

Interested in learning more SAT test prep in Cambridge and New York?

Want to read more on Cambridge Coaching Boston and SAT tutors?

Comments