Counting is hard.

At some point or another, virtually every business school aspirant stares down a GMAT quant problem that requires more mileage than what finger-counting can provide.

Consider the following sample question (courtesy of The Economist):

A plant manager must assign 10 new workers to one of five shifts. She needs a first, second, and third shift, and two alternate shifts. Each of the shifts will receive 2 new workers. How many different ways can she assign the new workers?

A) 2430

B) 2700

C) 3300

D) 4860

E) 5400

Take a minute or two to give this a go on your own. (Hint: the alternate shifts aren’t ordered!)

Don’t worry, I won’t keep you in suspense for much longer…because none of the answer choices are correct.

Perhaps, you find it surprising (if not ironic) that such a reputable organization’s inbound marketing material (for a GMAT test prep service) would contain such a mistake, but as someone who’s been burned by his fair share of tricky counting problems, I think blunders like this simply confirm that counting is hard.

Let’s use this problem to build intuition via narrative and to more deeply grasp what’s at play.

Stories you can count on

Story-telling is a fundamentally human undertaking and I find that this powerful tool helps to connect the dots between the seemingly cryptic formulae often associated with advanced counting and the underlying structure of the problem at hand.

The plant manager

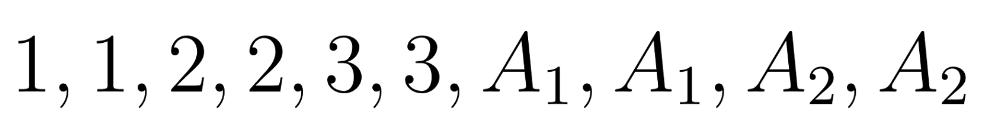

Put yourself in the shoes of the plant manager. Your 10 new hires are gathered in a line on the plant floor, awaiting their shift assignments. You look down and notice that you’re holding 10 slips of paper, each corresponding to a particular shift:

You think to yourself, “If I go down the line and hand these slips of paper out to the new hires (say, from left to right), the shift assignments will have taken care of themselves!”

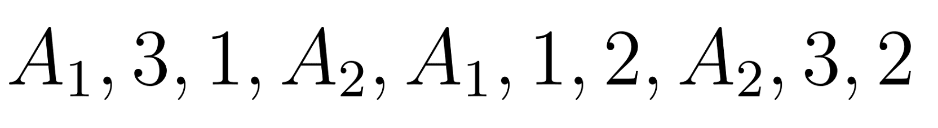

You may decide to distribute the slips in the original order or jumble up the order of the slips, yielding a different assignment of shifts to workers, e.g,

Great! We can order slips of paper in 10! different ways, right? Hmmm…not quite.

The new hires

To see why there is still work ahead of us, imagine you’re one of the new hires standing third in line. Using the mixed up arrangement from above, this would mean you received a 1; you’re on the first shift. It just so happens your brother is sixth in line, and he is also assigned to the first shift. If you two were to have lined up in each other’s place, would the plant manager have cared (or even have noticed)? Nope; you two would still be on the first shift.

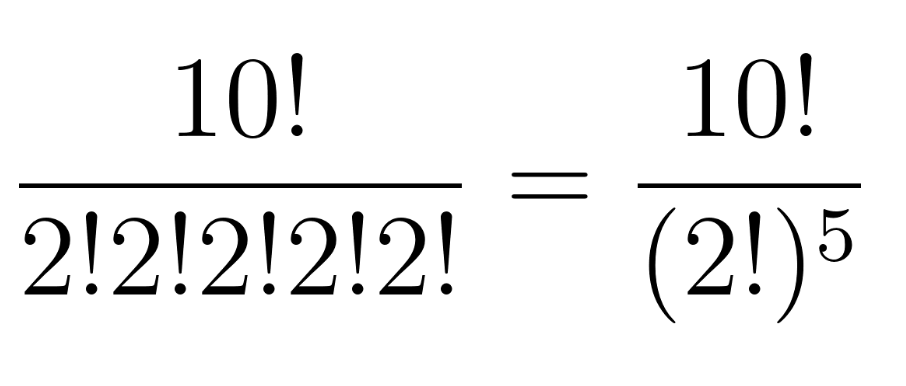

10! assumes each of the slips are unique, but we know that this just isn’t true: a 3 slip isn’t different from the other 3 slip in the same way you and your brother notionally switching places in line didn’t change the outcome from the plant manager’s perspective. We correct for this overcounting by dividing out 2! for each shift pair:

Why divide by(2!)^5? First, imagine there is a taller and shorter new worker for a given shift. Then, suppose we didn’t divide out by 2! – we’d still be counting the case where the taller of the two lined up first and the case where the shorter person lined up first as two separate cases. But we know that this pairing is the same, so we divide 10! by 2! to only count 1 of every 2! = 2 x 1 = 2 arrangements whereby the people comprising the pair could’ve switched places. Since there are 5 shifts (i.e., 5 shift pairs each consisting of a taller and shorter new worker), we make sure to do this division 5 times.

(Still confused? Try your hand at a similar problem first: counting the distinct ways to arrange letters of a word/name.)

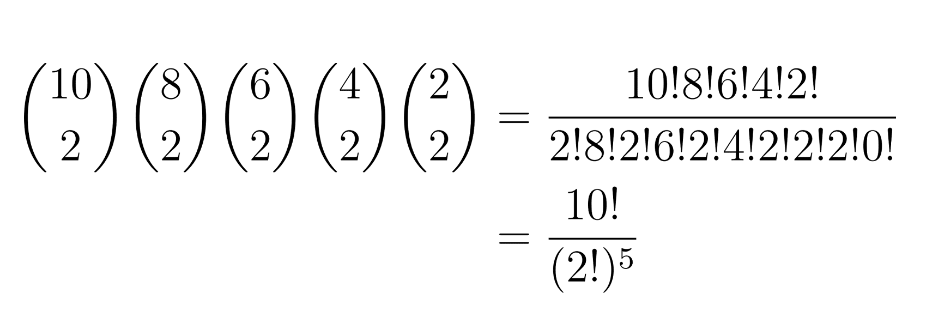

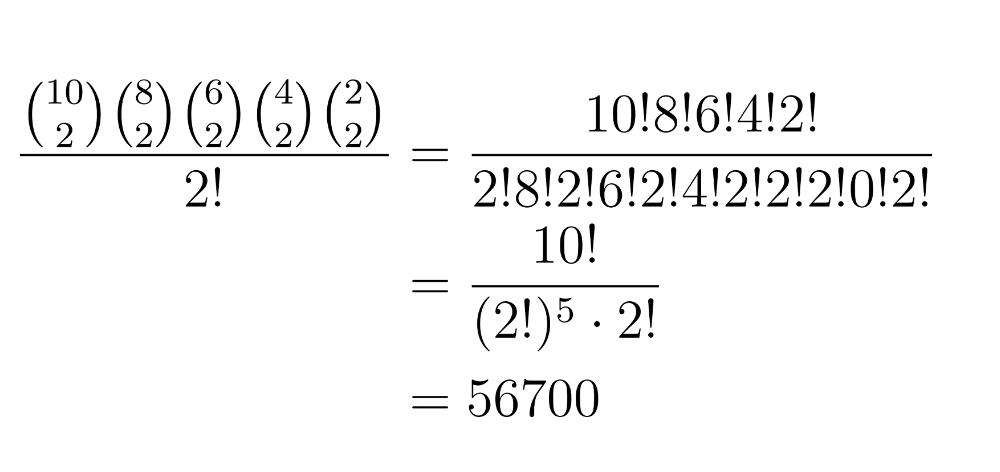

An observant reader might notice that our result is equivalent to using the “combination without replacement” formula (A.K.A. the binomial coefficient) repeatedly:

This tells the same story, but with slightly different language: we first count the ways to choose 2 plant employees among 10 (for the first shift) and then multiply by the number of ways to choose 2 among the remaining 8 (for the second shift), repeating the process until we don’t have any employees to assign.

At this point, we’re actually very close to being done. Importantly, however, the plant manager doesn’t care to distinguish between the two alternate shifts, which adds a wrinkle to the problem.

The alternates’ basketball run

Now, let’s pretend you and your brother received A1 slips of paper and your best friend and their sister are holding onto the A2 slips because the plant manager knows you four are the best hoopers among the new folks. Why is this relevant, you ask? One reason might be that the plant manager enjoys watching the alternate shifts play each other 2-on-2 during the lunch break, but another (more germane) reason highlights where else we’ve still overcounted.

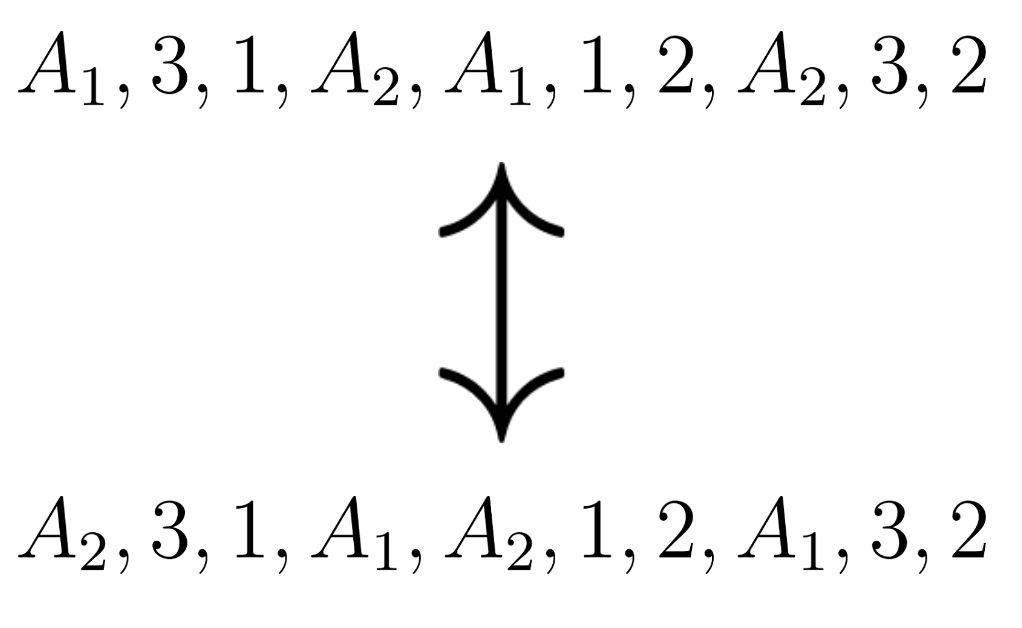

So far we’ve distinguished A1 (the “first” alternates) and A2 (the “second” alternates), but the plant manager makes no such distinction between the two alternate shifts. In the same way that you + your brother versus your best friend + their sister is the same game as your best friend + their sister versus you + your brother (in the context of pickup basketball), so too are the alternate shifts the same (as long as the two pairings are preserved). For example, the following arrangements are equivalent in the plant manager’s eyes:

Here the alternate shift pairings are the same (read: you’re still paired with your brother), but the [contrived] labeling of A1 and A2 are switched. Because we took care of the arbitrariness of two new employees’ ordering within a given alternate shift (read: you + your brother is the same as your brother + you) in the step above (i.e., two of 2!s in the denominator), we’re finally done once we divide out by one additional 2! to deal with the overcounting from permutations of alternate shifts (or pairs) themselves:

Count on it

Congratulations on finishing the story!

What we did was more than answer the question – we also demonstrated (via narrative) why our solution is correct. Of course, there are always multiple ways to tell/interpret this story. How might I tell the same story if, instead of starting with A1s and A2s, we started with 4 slips of paper labeled A(in addition to the numbered shift pieces of paper)? What adjustments would we need to make? (Be sure to leave your thoughts in the comments below.)

Don’t worry if this still feels foreign! You will hone your sense for recognizing the structural similarities across counting problems and these stories will emerge on their own with practice.

Comments