The dementia spectrum is enormous, spanning a complex range of cognitive, pathophysiological, and social factors which vary from person to person. We pour billions annually into research—trying to get to root causes and fund clinical trials—but for most conditions, we’re far away from a cure. Treatment is usually focused on symptom management and therapy: trying to slow the decline and helping patients maintain a high quality of life.

In this setting, early diagnosis is crucial. The sooner someone is diagnosed, the sooner they can work with their doctor to start on a treatment plan, and the easier it’ll be to navigate daily life going forward. For well-studied diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, research has shown astonishing differences in treatment effectiveness based on the stage of diagnosis. The problem is that early warning signs—memory troubles, periods of confusion, changes in mood or energy—can be subtle and hard to pinpoint until the disease progresses to a more advanced stage. The goal of routine screening is to pick up on these signs before it gets to that point.

Gold standard screening tests: MoCA and MMSE

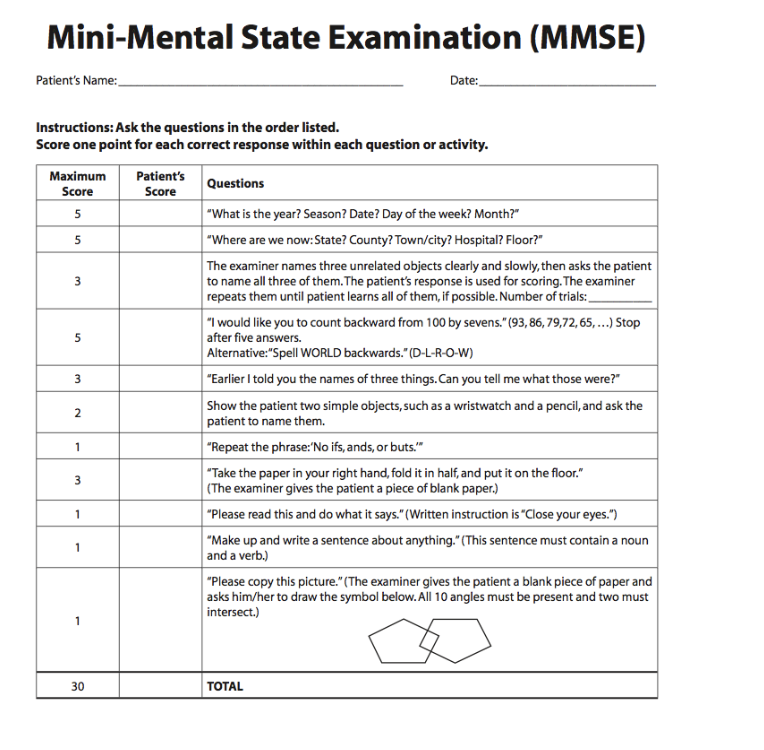

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) are the two standard screening tests used in hospitals everywhere to check for signs of cognitive impairment. They are scored out of 30 points and are intended to take about 10 minutes to administer. (In practice, they can often take much longer, up to 30 minutes.) Take a look at the MMSE, pictured below:

There are several reasons why this sort of test is very useful. It’s quantitative and standardized—so you can compare numerical scores between different patient groups as well as track an individual patient’s progress over time—and it also differentiates between different cognitive/motor domains (e.g. spatial function, language, memory). The test is easy to score, and hospitals use standardized score cutoffs to determine whether to refer someone for further treatment.

Shortcomings

Despite their upsides, tests like the MoCA and MMSE have some very clear weaknesses. Here, we’ll talk about a few important ones.

Lack of Change.

The MoCA and MMSE were developed in 1992 and 1975, respectively. Though there have been some adjustments made since, both tests have remained relatively unchanged over the past decades. While this can be a good thing (it allows for comparisons between tests taken many years apart), the inflexibility can lead to the test becoming outdated in light of new research and clinical knowledge.

Time.

These cognitive exams can take the majority of the time in a typical 45-minute appointment with one’s physician. That leaves less time for things like screening for motor issues, conversation, and creating a plan—all which could be just as useful.

‘Summary’ Scoring.

Each cognitive domain (e.g. “memory”) is represented by only one or two test items, which may not truly capture the tester’s underlying ability in that cognitive domain. Additionally, though individual scores per test item are calculated, only the total score typically goes into the medical record (and is used for determining whether further treatment is needed). Combined with natural test-retest variability in overall score, this can make it difficult to identify where exactly declines are occurring.

Lack of Adaptivity.

These tests are non-adaptive, meaning that everyone gets the same test items regardless on how they performed on previous portions of the test. If a particular task is way too easy (or way too hard) for the tester, it won’t be very helpful in assessing whether their true ability has stayed the same or declined over time. In contrast, an adaptive design calibrates the difficulty of each item to the tester’s ability (as estimated by performance on earlier portions of the test), ensuring that the response to each question is actually informative.

A New Approach

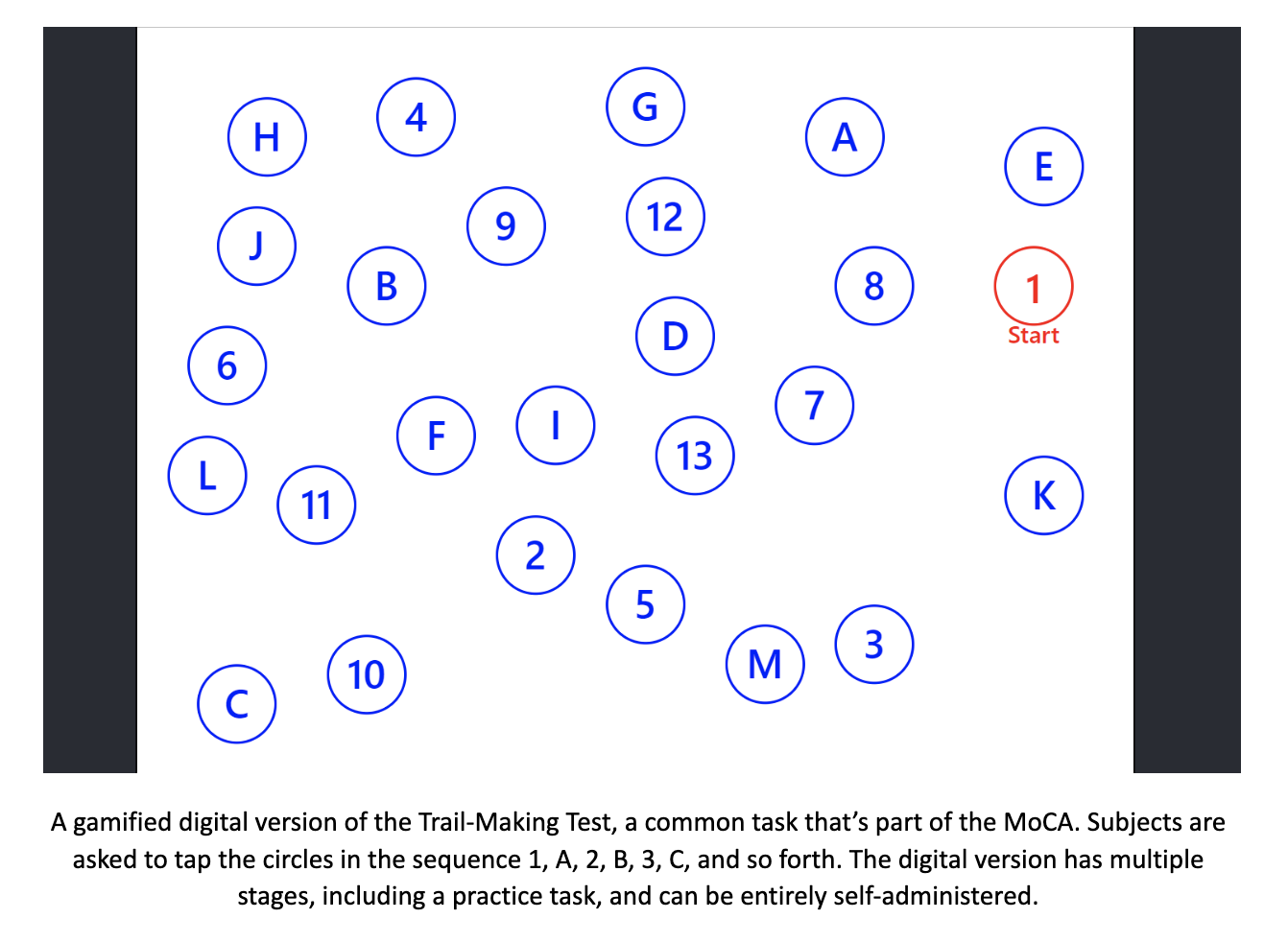

In the past few years, there’s been a new wave of digital screening tests that aim to overcome the shortcomings of their paper-and-pencil counterparts. Backed by rigorous data analysis combined with clinical experience, these tools may offer a level of adaptivity and precision leagues beyond that of conventional exams. Instead of arbitrarily assigning whole-number point values to test items, performance scores on each subtest can be calculated using mathematical techniques like item response theory (IRT) and maximum likelihood estimation. Administered on a computer or tablet, they can be made into games—rather than stuffy paper/pencil tests—allowing for an enjoyable experience which also saves time. Below is an example of one such project, the Boston Adaptive Assessment Tools, which I’ve been fortunate to be a part of developing.

Though these digital screening tools still need to overcome a number of hurdles—technological anxiety, validation and norming, scaling—they represent an exciting new approach that could help improve the diagnosis and treatment of dementia worldwide. Personally, I’m quite excited to see where this field goes in the coming years!

Comments