I’m not a visual learner. I’m not a “diagram person.” I was a skeptic when first introduced to concept mapping. It was not a tool I made use of until the very beginning of my fourth year of medical school right before I took my second board exam, but it was something I wish I’d known about long before when taking college exams or the MCAT. While they’ve been increasingly used in the last few years, concept maps have yet to reach their peak. I expect them to be ubiquitous in classrooms in the next decade or so because of their ability to help all types of learners and tie big-picture concepts together while still retaining detail.

Here are some of the high points I’ve learned about concept mapping:

1. Concept maps are not algorithms.

Whereas algorithms are if-then statements that lead to decision making (if someone is pulseless, then start CPR), maps are more conceptual and more about the relation of different ideas and parts.

2. Concept maps are not unidirectional.

They are bidirectional, and can make sentences in both directions. Say, for example, we’re making a concept map about the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone-System response to hypotension. You might have one branch coming off for renal hypoperfusion, and another for arterial baroreceptors. Hypotension will cause a response in both of these, but you can also work backwards to remember that these will be active during hypotension. From renal hypoperfusion, you may have two branches – one for less pressure felt by the afferent arteriole, and one for less salt delivery. In being bidirectional, the map flows in both directions so that a test question or clinical problem can be thought through from the top-down or bottom-up. You can also draw arrows across various points; e.g. in a map about acute injury, you may have pre- and intra-renal as two separate branches, though if a prerenal injury persists long enough it will lead to intrarenal disease as well.

3. They work best if you make them yourself.

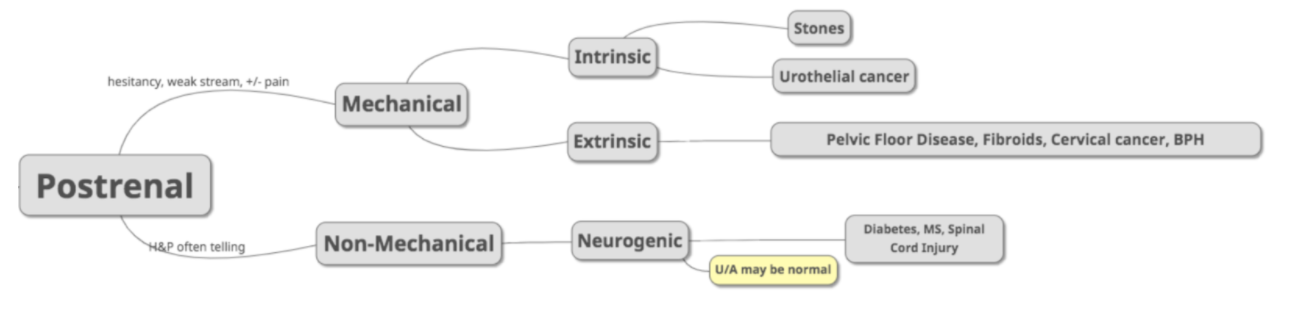

Information is best retained if you think through it yourself and form your own connections. I recommend mindmup.com – it’s the Prezi of concept mapping, and very user friendly. As an example, below is a photo of an Acute Kidney Injury map I made on the site. It’s a rather large map, so for simplicity I’ve just included the post-renal branch. If you’re looking to use others’ pre-made concept maps, the University of Calgary is a fantastic resource with many large maps.

For the first course of my last year of medical school, I took a class dedicated exclusively to clinical concept mapping. Going through the motions of the course, I wasn’t sure if I was retaining any new data or associations. I took my second board exams at the end of that class and jumped over twenty points (more than a standard deviation) as compared to my first; in retrospect, I'm certain that this leap was due in part to the associations and fluid thinking that the maps had taught me.

Comments