One thing I wish I had learned as an undergraduate (who geeked out on medieval lit) was how to find and read facsimiles of original manuscripts. The Internet is a treasure trove of public works, with classic, canonical, and contemporary literature available in html or as PDFs. This is awesome. It meant I could teach a survey course of British literature without asking my students to buy a single book.

Also available but less well-known, however, are vast archives of digitized historical manuscripts and early printed works. (Just for reference, a manuscript refers to a handwritten text, which was the most common mode of production through the medieval period. Printed works weren’t standardized and mass-produced until the nineteenth century. From roughly Renaissance through Enlightenment, then, books were costly and unique objects that varied from printer to printer).

Digitizing early texts is an ongoing effort that requires painstaking labor and special care. Scholars, librarians, (and probably a lot of grad students), who are trained to handle historical artifacts, copy manuscripts and early printed works page-by-page for eventual online access. Such works are usually available through your university library in databases like Early English Books Online (EEBO), Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO), or Nineteenth Century Collections Online (NCCO).

Because these works are either handwritten or in non-standard print, the reading experience is completely different, and we can’t rely on digital means of analysis (e.g. Ctrl+F to determine how often a given word appears). The benefits far outweigh any inconveniences, however, because working with a facsimile of an original text opens you to the experience of its original readers.

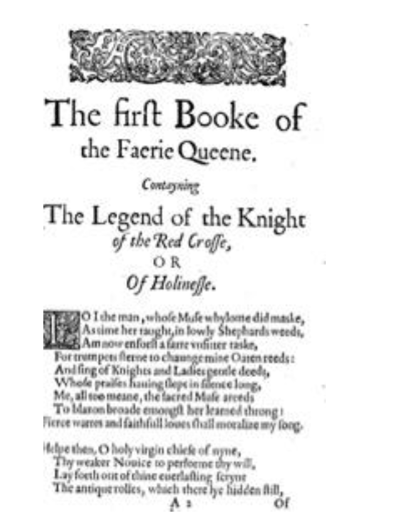

Take the following example, which features the first canto of Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene (1590) in its first printed edition, versus a modern PDF available on Project Gutenberg:

These examples offer ample material for discussion, but here I’ll just point to a few questions that might arise for a modern reader when viewing the facsimile of Spenser’s text. The engravings are visually arresting, and a student might wonder what they signify, how they inform the poem, or who produced them. This would require some research, and a new student to early English literature would learn that the illustrations were engraved in a sheet of metal, which was then covered in ink, wiped with a cheesecloth so that ink only remained in the engraving, and then stamped onto the paper by the printmaker. This alone offers a glimpse into the complex, collaborative process of early bookmaking, and generates more questions. Did the author choose the illustrations? Were engravings standard at a given printmaker, or custom-made for each book? A student would notice that the ‘s’ character resembles an ‘f’ unless it is used to pluralize a word, and that there is no ‘u’ character, but ‘v’ is used for both. They might wonder whether this choice was economic or stylistic, and if it pertained to handwriting as well.

If a student browsed other facsimiles from the same period, they would quickly realize that spelling, typeface, and capitalization were not consistent across texts, but the unique choices of each author and printmaker. If a word appears in italics or all-caps, it could be the author’s designation or the printmaker’s interpretation. This highlights the extent to which the printmaker was responsible for the aesthetic resonance of the text, who transformed the author’s manuscript in a sometimes-contentious negotiation process! All of the unfamiliar elements in a historical facsimile offer the modern reader an opportunity for new knowledge. They are invited to note the distinct historical markers of a text, and eventually they will be able to discern the printmaking conventions of one period from another, just as they might distinguish a Gothic cathedral from a neoclassical courthouse.

Rather than a modernized PDF, which streamlines the text for ease of reading, an original historical document asks the reader to meet it on the terms that it was produced. This gives us infinitely more insight into the material conditions and aesthetic hallmarks of a given period, and illuminates our own, which we may have taken as natural. Perhaps most importantly, the highly stylistic elements of pre-standardized texts remind us that for most of human history, literacy was uncommon. Information was communicated orally, meaning books were rarefied storehouses of knowledge, but also visually, which helps to explain the devotion to pictures and symbols in early literary works. As literacy became more common, images faded from the text.

While online archives are humdrum resources for humanities graduate students, they are often unbeknownst or intimidating to undergraduates. If you’re in any kind of course that engages pre-twentieth-century texts, I would highly recommend diving into the rich world of digital archives. They contain hundreds of thousands of texts that will never be printed or converted to html, which makes them a goldmine for untapped historical knowledge. Most importantly for any student of history or literature, facsimiles of early texts offer a window into the imagination, material resources, technologies, and traditions of the people who comprised the period.

Comments